What is the right to be forgotten (RTBF)? According to Insurance Europe, “A RTBF requires insurance to be offered without considering all relevant risk factors.” [1]

In recent years there has been increasing focus on potential discrimination against cancer survivors in the application of life insurance for home loan or other credit protection.[1] Therefore, in 2021 the European Commission published ‘Europe’s Beating Cancer Plan’, stating that Europe needed renewed commitment to cancer prevention, treatment, and care.

Buried in the section entitled ‘Improving the quality of life for cancer survivors and carers’ is a statement about access to financial services, which includes insurance, to ensure fairness in the treatment of cancer survivors who are in long-term remission. The Commission wishes to ensure that “only necessary and proportionate information is used when assessing the eligibility of applicants for financial products, notably credit and insurance linked to credit or loan agreements.”[2]

In 2020 there were 2.7 million people diagnosed with cancer in European Union countries, and it is estimated that there are over 12 million individuals who are ‘cancer survivors’. [2] In order to address this challenge, the recommendation is for a Europe-wide ‘right to be forgotten’ code of conduct.

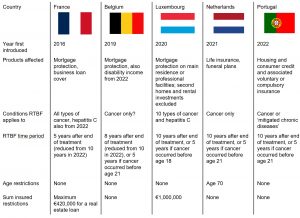

Let us look at the current situation in five European countries.

Image: Paper – Right to be Forgotten framework for Cancer Survivors | Society of Actuaries in Ireland

While there are certain similarities between these legislations, the significant differences are the time since the end of treatment and the breadth of coverage. Recent changes to RTBF legislation in France not only reduced the time period from ten years to five years, but additionally allows for mortgage protection and credit insurance of a value up to €200,000 to be accepted without medical underwriting, provided the term does not extend beyond age 65.[3]

In France, Belgium, and Luxembourg it is the responsibility of the applicant to decide whether they need to declare their medical history, whereas in Belgium all information needs to be disclosed, and it is the responsibility of the insurer to decide whether the information is allowable under RTBF guidelines.

The law in Portugal also covers chronic disorders such as diabetes and even mental health, embracing any “pathology that determines a long-term, evolving, potentially incapacitating, organic or functional alteration that affects the quality of life on a physical, mental, emotional, social and economic level and is a potential cause of early disability or significant reduction in life expectancy.”

As may be understood from the brief summary above, the situation is complicated. Even those within the industry are challenged by multiple different guidelines, let alone potential applicants, particularly where the onus is on them to decide whether it is necessary to disclose certain parts of their medical history.

The insurance viewpoint

Probably for as long as private insurance has existed, underwriters have used an individual’s medical history to assess risk. The tenet that underlies insurance is the ability of the insurer to assess the risk and to charge the appropriate premium to cover that risk.

So, when legislation like RTBF is introduced, it throws this principle into disarray. If applicants who have experienced various forms of disease can avoid having to declare their medical history, is an insurer then at a considerable disadvantage when it comes to assessing the risk?

Protagonists of RTBF state that it is only fair to treat cancer survivors in this way, saying that insurers typically utilise outdated information to set premiums, and suggesting that according to the most recent research, cancer survivorship is increasing, and survivors are experiencing a similar life expectancy to others of the same age and sociodemographic status who have no history of the disease.[4]

Whilst it is likely true that insurers largely use retrospective data to derive rating guidelines, this is a necessary part of the process. Thinking about the process of risk assessment, at the time of application there is a one-time chance to judge whether the life proposed is eligible for the standard rate of premium or whether there is an increased risk requiring a higher one. This is not an easy task, especially given that the typical policy term is 20 to 25 years. This is where the utilisation of long-term survival data is vital to enable insurers to develop an understanding of the long-term risk.

Let us take breast cancer as an example. The RTBF guidelines in France are complex, and only allow for cancers that are either in-situ or stage I invasive tumours to fall under the legislation. But research shows that even stage I cancer can recur as long as ten years after diagnosis and treatment. A notable example of the long-term mortality risk associated with breast cancer is that of the singer and actress Olivia Newton-John who died in 2022, some 30 years after her initial diagnosis. While we do not know what staging was applied to her initial tumour, this is an example of the long mortality tail associated with breast cancer; some researchers even suggest that it should be treated as a chronic rather than an acute disease.[5,6]

With all cancers, not just of the breast, there is also the challenge of understanding the histology and then the sub-type, and maybe several layers more of differentiation to tease out the true prognosis. It is not suggested that underwriting guidelines will cover all these eventualities, but it is necessary to be mindful of the layers of complexity faced when trying to understand the true level of risk.

Suppose every person who applied for cover of $100,000 over a term of 20 years paid the same premium regardless of their level of risk. It would result in much higher premiums for most people (who would have been accepted at the standard rate of premium) and lower ones for those who are at the highest risk. This is contrary to the principle of equity between policyholders and to that of treating customers fairly: those who are healthy lives are penalised by paying increased premiums to subsidise those at a higher risk.

Therefore, individuals at higher risk, with a greater chance of claiming, will view the insurer’s offer as a bargain, and likely will apply in higher numbers than if traditional underwriting were in force. This, of course, is anti-selection at work, and will mean that premium rates will have to be increased again, further disadvantaging the healthy lives – who may just decide that premiums are poor value for money, or even unaffordable. Making insurance less accessible to all groups would be an unintended and undesirable consequence.

There are, however, opportunities for the insurance industry to work alongside the architects of any Europe-wide code of conduct on RTBF to ensure that it benefits consumers as well as providing a viable framework for the insurance industry.

Closing thoughts

Many if not all of these changes in legislation are designed to protect the consumer and make access to insurance more equitable. However, it seems that in some instances the opposite effect may be the final outcome. It is vitally important that insurers are seen to treat customers fairly, and although the whole process of underwriting involves differentiating between different classes of risk, insurers need to be able to utilise all relevant information to allow fairness and charge the right premium for the risk.

Removing the ability to do this by restricting the amount of information an insurer is permitted to utilise in the underwriting process runs the risk of increasing premiums for all and those who would normally be accepted at standard rates paying more to subsidise higher-risk individuals.

Insurers must work with legislators to protect their right to underwrite, and legislators should be mindful of the need for fairness and equity to ensure that coverage remains accessible and affordable to as many people as possible.

This article focuses on Europe, but the concept of RTBF may, in due course, arise elsewhere too.

- https://www.insuranceeurope.eu/priorities/2473/risk-based-underwriting-incl-ec-beating-cancer-plan (Accessed 24 July 2023)

- https://health.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2022-02/eu_cancer-plan_en_0.pdf (Accessed 24 July 2023)

- https://web.actuaries.ie/sites/default/files/story/2023/04/310331%20SAI%20RTBF%20Working%20Group%20Report%20final.pdf (Accessed 16 July 2023)

- Scocca G, Meunier F. A right to be forgotten for cancer survivors: a legal development expected to reflect the medical progress in the fight against cancer. J Cancer Policy 2020;25:100246.

- https://www.aeras-infos.fr/cms/sites/aeras/accueil.html (Accessed 24 July 2023)

- Kamata A, Hino K, Kamiyama K et al. (March 03, 2022) Very late recurrence in breast cancer: is breast cancer a chronic disease? Cureus 14(3):e22804. DOI 10.7759/cureus.22804